Impasse

I noted two things that would appear if not contradictory then at least antagonistic: I said that it was possible – though maybe I should have said ‘not-impossible’ – to consider ‘change’ as the key concern of Badiou’s entire oeuvre, thus making some claim to there being a consistency across the oeuvre. I also said that the oeuvre is constituted by an immanent divide.

There is the pre BE work and the post BE work. This requires that we have some concept of BE as the formalisation or concretisation of such a divide which would then make everything before either, relative to the oeuvre at least, come to inexist or be consigned to a historical register, an archive, something to be mined, essentially, for what it might point to in the present situation but itself having no autonomous purchase on this present. The latter in turn provokes a sort of historiographical excess, commentators arguing over the history of the history itself – thus ‘university debates’ arguing for the continuity or the division.

Given we are working somewhat at least within the discipline of philosophy – now there is a word we have learned to unhear – we should try to figure a concept that can account for what I am calling an immanent division: something that can think the Two without reducing one to the other or establishing, as university debate cannot not do, a two sides to the story narrative wherein we either maintain an opposition and endlessly elaborate it or we become partisans of one side or the other, posing authentic or radical in the face of all the other comers – such is the university discourses form of self-flattery. Either way, we are not inside the work and being inside the work, thinking the thought it is and not treating it as ‘object’, is Badiou’s method.

How can we think this pre and post BE (dis)continuity? That between the deployment of poetry, mathematics, love and politics without condition and the deployment of them as conditions. Badiou himself considers his work in philosophy at least – which, so defined, is the site of the compossibility of these conditions – as going from BE to IT. The proliferation of smaller books, post 1988, all put into demonstration, relative to the variety of topics addressed, the concepts and categories created in BE first, and the other big books since. In two post IT oeuvre summaries, Sometimes, We are Eternal and Badiou by Badiou, TS doesn’t get a mention and this is pretty consistent. The times when he does speak about TS are usually when he is asked directly. And when asked he doesn’t disavow that work but he does periodise it, so to speak.

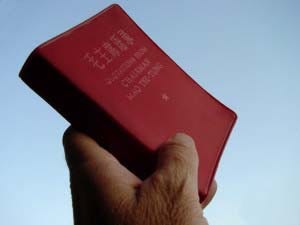

All this anyway is relevant only because, if we are approaching Badiou as a philosopher then we have to accept that as a philosopher what he invents in philosophy is under condition; under condition of the truths of its time. Which is, post BE, axiomatic for what is philosophy. But in TS we also see the concern with truth albeit, and this is the point, the truth of politics only, which means there, the truth of Marxism. Hence: ‘Maoism is the Marxism of our time’; ‘the thought and practice of proletarian revolution…’: ‘Today’s political subject [is] that of the Cultural Revolution, the Maoists” (TS) hence: ‘there is only one great philosopher of our time: Mao Zedong’ (The Actual Situation…). Finally, from TS: 'Every subject is political. Which is why there are few subjects and rarely any politics.’

So politics conditions the philosophy that is TS which is the putting into form the efforts to think and practice proletarian revolution – the truth of Marx, the force of Mao. But it’s not a condition. It is suture – politics does philosophy or is philosophy as such. Philosophy has abdicated or delegated – handed over the whole of thought to one generic condition.

Badiou asserts as much at the time. Indeed insist on it. And this is how we have to understand the panoply of discourses and thinkers that populate TS – Mallarme, Holderlin, Cohen, mathematics, set theory, psychoanalyses and so on all generating the conditions for a (renewed) politics whose subject must be found.

But Badiou doesn’t at the time consider this an abdication and so TS has not betrayed the definition of philosophy that BE institutes. Even if that definition would not count TS as philosophy. In his collection of essay published under the name Conditions, he says, thinking back to the period TS treats with, 'Today, I would no longer say "every subject is political", which is still a maxim of suturing. I would rather say: "Every subject is induced by a generic procedure, and thus depends on an event. Which is why the subject is rare.’ And in MP; 'Every subject is artistic, scientific, political, or amorous. Besides, this is something everyone knows from experience, for outside of these registers, there is only existence, or individuality, but no subject.’

A key thing to note in all this especially concerning the question of change, is how to combine a rigorous formalism with regard to situations or worlds – an inheritance from structuralism; modified by his return to Plato – with some (new) concept of the subject – an inheritance from Sartre; modified by May 68 – as always the exception to that structure and that, then, in its working through this same situation, changes it.

In IT, he describes TS in summary as saying: ‘a genuine politics must be rooted in movements and risky ventures and must at the same time invent new forms of discipline and organization.’ Summarising BE he says: ‘The idea that the subject is constrained by the formal rules of an underlying ontology is based... on a theory of multiplicities formalized by the mathematics of sets. That the subject is also, however, an exception to this constraint takes the form of an unforeseeable origin, a local rupture, which I call an event... the work of the subject is woven, faithfully, out of the consequences of the event within the very order whose law it has disrupted, gives rise to the concept of truth. Thus, every subject is a participant in a truth, which is an immanent exception to a particular situation’.

In LW, provoked by Jean-Toussaint Desanti’s suggestion concerning the expansiveness of Category Theory as a formal theory of relations he took up the next stage of the question: how truths may appear and really exist in a particular world. ‘I had previously investigated truths and their subjects as post-evental forms of being. Now I investigated truths and their subjects as real processes in particular worlds, as existential forms of what nevertheless has universal value.’ And in IT: ‘what about truths and subjects, grasped, beyond the structural forms of their being and the historico-existential forms of their appearing, in the irreversible absoluteness of their action and in the infinite destiny of their finite work?’ IT 24/5.

If we are not subjects we are ordinarily inhabitants of situations, creatures of structure, bodies for worlds, animals of God or Nature: or, riffing from Aristotle, featherless bi-peds whose charms are not obvious…

My contention is that we speak of the division between pre and post conditional philosophy in terms of the impasse: that with TS we see Badiou go as far as he can in the direction of thinking true change (and thus what in the situation of the time makes it impossible) as determined by the suture of philosophy to politics. Impasse as aporia in the Platonic sense; the point not of defeat but of a recommencement. That is: ‘Yesterday’ we ruled out A, B & C as being determinative of the truth of X. We didn’t determine the truth of X but we now know more of what it is not than we did yesterday.’

And as mentioned already this is precisely how TS ends – in true aporetic fashion; that this exhaustion which is the text of the failures of The Red Years announces ‘in confidence, as in truth’ – this is the eve.

Red Years.

Badiou is very fond of this phrase ‘The Red Years’. Sometimes the dates are varied by a year or two but they cover the decade from 1966 to 1976 – from Mao’s incredible document, Decision of the Central Committee of the

Chinese Communist Party Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (‘The Decision in 16 points’), which doesn’t begin the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution but founds it, and runs to Mao’s death and the reversion, under Deng, once called the ‘number two capitalist roader’ in the party, to a more steady state ‘communism’. Of course these cover the years in France for which May ‘68 is the crucial focal point for a working politics.

In The Communist Hypothesis he broadens this and says: the red years were ‘ushered in by the fourfold circumstances of national liberation struggles (in Vietnam and Palestine in particular), the worldwide student and youth movement (Germany, Japan, the USA, Mexico . . .), factory revolts (France and Italy) and the Cultural Revolution in China.’ (1) ‘It was then’, he says, speaking of May, ‘that I learned what politics really was: a shortcut to the essential and neglected segments of a changing society, an organic link with factory workers, low-level employees, and especially the masses of proletarian newcomers...’ IT 24.

The Red Years also end where TS, the work comprised of seminars given between ’75 and ’79, and published in 1982, pretty much begins. TS is something of an attempt to formally render the ‘balance sheet’, as they used to say, of all these years, in the context of French Maoism, actual, daily, political work, post 1968. Badiou periodises the decade: ‘from 68 to 71 the years lent themselves to the most real and simple philosophy, of revolt, the one that forms a single body with the practical question of the revolution. In the heat of the moment people worked on One divides into Two: the class origin of ideas to bring down the reign of the mandarins; antagonism and non-antagonism were distinguished in order to push to the end the workers struggle against the PCF and unions; identity and difference referred back to the place of the organised Maoists in the movement and to the inventive force of the popular masses’ (The Actual Situation… AFP, 4).

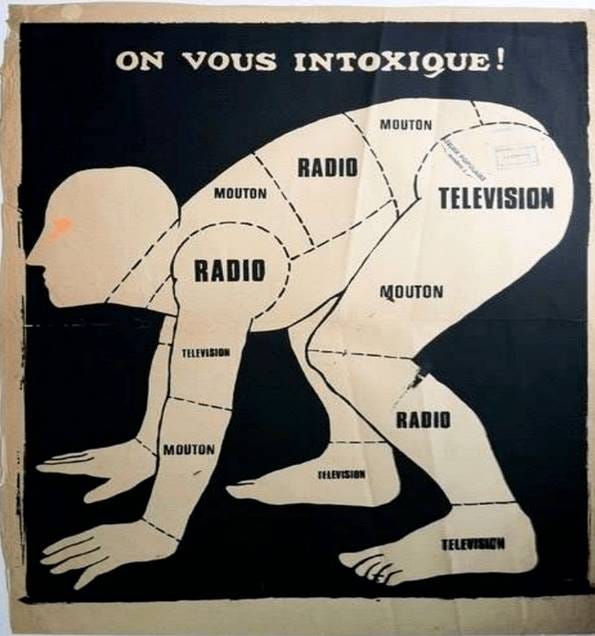

But it also means settling accounts with a whole series of failures, compromises, revisionism and renegacy. In ‘The Actual Situation on the Philosophical Front’, from 1977, just cited, he recalls that from 1972, coincident with the left groups signing onto what was called ‘the common programme’, realised in Mitterrand’s election in 1980, there appeared, in the guise of philosophy, a series of ‘the enemies of all thought’. Under the invariant question of ‘What happened to us? – a question relative to the commune of 1872 as to 1917 as it is to the GPCR and to ‘68 – and restated here as ‘what happened to Marxism’, – Badiou provides one of those magnificent lists that you find throughout his work of the variants that make up this reactionary enemy, (ASPF 2-3)

Quote … ……………….

So these are the avenging virtues of the ‘philosophies’ over the event of ‘68. Lovers of revolt, constituted in a ‘pure, idealised masses’, but not so much of the subject it brought to the stage: the masses and the thought it demanded; organisation and discipline. Hence, for Badiou, a philosophy devoid of this subject, the true subject of what alone is politics, takes up by default the cause of one bourgeoisie or another: sort of like how our democracies work. Note, ‘philosophy’ is used here to denote the petty bourgeoise intellectual.

That’s to say, if you take the antagonism out of it, which the event of the masses brings to the stage as the true subject of politics, then you have merely negotiations over programmatic interests – one demanding increased productivity, the other higher wages for the increase in productivity - to use an example we are all depressingly familiar with. Two makes one we can say. These are the tasks of administration and management that, in his Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism, he says ‘the politcal’, in all it’s finitude, names today.

Philosophically speaking and in the context of the time, Badiou asserts that what the enemies of thought devolve to, thus paralleling in philosophy the common programme, is either the position of Desire or the Angel. In the first, desire subsumes any notion of antagonism within something like a permanent, libidinal revolt – a flux. The dialectic is undone in favour of the negotiable multiplicity of invested positions. On the other, the figure of the purified agency of the Rebel. A theologism basically; Christ without Paul. Pure event, no subject. So in both cases, then, the masses are ruled out of making history – this is the material point as subject. They are cypher or the crucified. And this is done so variously as he describes in ‘The Actual Situation on the Philosophical Front’. And this variety is the false dialectical fluff of university discourse to this day.

Maoism, as the only philosophy, as he declares in this period, against all these natural philosophies – rhizomes as much as arborescents – is the dividing in two of this renegade ‘two as one’ configuration of what is the philosophical front post May ‘68. We should emphasise that the events of May open up the situation to multiple possibilities. ‘Those who, like we did, saw in the first place a lack (the subjective and political precariousness, the absence of a party) and not a fullness (revolt, the masses in the streets, the liberation of speech) had something on which to nourish their confidence, while the others had nothing left but the possibility of betraying their belief’ (TS 327).

What is at stake, for Badiou and his comrades, is forcing the consequences of this event in to the situation; not so much in opposition to any one of these other possibilities but as a manifest and militant indifference to them all; establishing what is generically to the event of ‘68, such that it is for all and thus it is what is true of the multiplicity opened onto the situation by the event; what it is not is the assertion or celebration of multiplicity as such. In a real but all too phantasmatic way, liberalism – and remember this is the period of the reassertion or restoration of liberalism but under post-modern conditions – maintains multiplicity as real, but as means. It approaches the subject of history as an object within the unfolding of the end of history – which is to say, the end of communism. We can say the agency of such an object – agency differentiates it from it’s mere daily conformity to the commodity form – will be an ethics.

The means are ‘constructive’. Which in Badiou’s meta-ontological framework means, it rejects the generic a priori. Hence everything is possible for the liberal because something other than what it determines to exist is impossible. The impossibility of the true is the post-modern condition. Under the paradoxical reign of representation or, if you like, ‘our democracies’ (but it extends further than just politics) identities and differences proliferate without concept, lived experience, that staple of what they used to call the human sciences, directs all treatment, and any configuration of the collective as disciplined, organised, and forceful, thus as subject is ruled out as precisely either non-representative of some experience or other or as unrepresentable as such, and so an illegal totalitarian style existence which must be treated as such. The two arms of the power of the ‘state’. Badiou and his comrades are diagnosing in the '1970’s what has become of us, vis a vis, in politics, the idea of communism.